Enlisting the Army to end corruption in the government’s construction projects

This piece is freely available to read. Become a paid subscriber today and help keep Mencari News financially afloat so that we can continue to pay our writers for their insight and expertise.

In many remote communities, where the security and safety of private contractors are not guaranteed, the government has been tapping Army engineers to build roads and other infrastructure. Many of these communities were infested by Communist rebels, Muslim guerrillas, and bandits who extort money from construction companies.

Thus, the Armed Forces needed to step in to complete the projects, which more often than not were funded by the Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH). For the government, sending the Army to plan and execute vertical and horizontal structures is cost-efficient.

No public bidding is required, no overhead costs for equipment and manpower, and no cutting corners. The Army engineers are as skilled and competent as the engineers in the private sector. That’s why Public Works and Highways Secretary Vince Dizon has enlisted the military’s help in investigating non-existent, substandard, and overpriced infrastructure projects, particularly flood control, roads, and school buildings.

Truth matters. Quality journalism costs.

Your subscription to Mencari (Australia) directly funds the investigative reporting our democracy needs. For less than a coffee per week, you enable our journalists to uncover stories that powerful interests would rather keep hidden. There is no corporate influence involved. No compromises. Just honest journalism when we need it most.

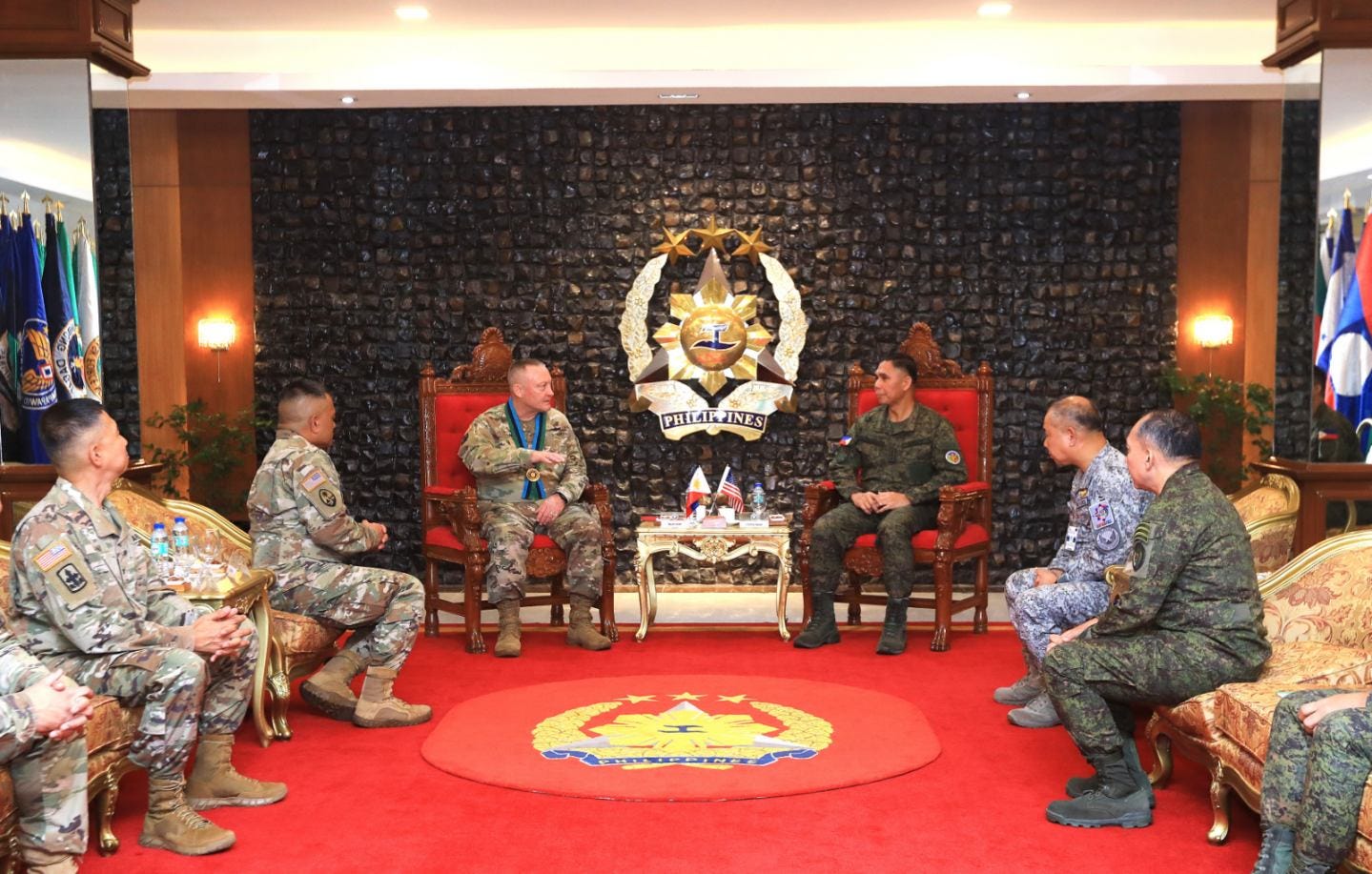

In the future, the Armed Forces chief of staff, General Romeo Brawners Jr. said the Army engineers will support the implementation of infrastructure projects in the provinces. The Army has five combat engineering brigades, distributed across Luzon, Visayas, and Mindanao, whose primary mission is to build military-grade structures at bases. But these units were also deployed to finish development projects in villages where there are active threats from rebel forces.

The Air Force and Navy also have engineering units that specialize in mission-oriented construction, like airfields and piers. In asking the military to oversee construction projects, Dizon aimed to end corruption involving politicians, government engineers, and private contractors.

At the Senate Blue Ribbon Committee’s public inquiry, Roberto Bernardo, a former DPWH undersecretary, said all the project’s public bidding are rigged to favor the politician’s choice construction company. Some of these companies are either owned by the family and friends of the politician, or had paid huge amounts to get the project, like the Discaya couple.

The Discaya couple had admitted bribing officials just to get the contracts, paying up to 25 percent of the project cost to politicians. Only about 30 percent of the project cost goes to the actual construction. The DPWH, other agencies, and other contractors also had a share of the kickbacks. As a result, most of the government’s infrastructure projects were sub-standard. The quality of the projects was sacrificed to satisfy the politicians’ greed for kickbacks.

Based on the testimonies at the congressional hearings, the collusion among politicians, engineers, and contractors was not an isolated incident that had happened in only one engineering district in Bulacan.

Since the number of projects already runs into billions of pesos in Bulacan’s first engineering district, the former district engineer, Henry Alcantara, said he asked other district engineers in Tarlac and Pampanga provinces to do the same scheme.

In his inspection trips in the provinces, Dizon discovered “ghost” projects and similar schemes involving politicians, the DPWH, and private contractors. It has become widespread that the annual budget for the DPWH was bloated to more than 1 trillion pesos this year. If only 30 percent was actually spent on the projects, the DPWH budget should be only 300 billion pesos.

About 700 billion pesos were lost to corruption. For next year’s budget, lawmakers must scrutinize the DPWH’s budget proposal and trim off the fat. That’s a tall order for Dizon. He has to clean the department and tame the greed of lawmakers. Dizon has dismissed, suspended, and filed cases against DPWH personnel involved in defrauding the government. He was hoping to recover the personnel’s ill-gotten wealth and asked the Anti-Money Laundering Council (AMLC) to freeze their assets.

For instance, Brice Hernandez, who earns 56,000 pesos a month, has more than 35 million in 36 bank accounts, drives a fancy car, and gambles in a casino. Dizon wanted to end this corrupt practice. He was hoping the Army Corps of Engineers would help him straighten out the government’s construction activities

The opinions expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of this publication.

Got a News Tip?

Contact our editor via Proton Mail encrypted, X Direct Message, LinkedIn, or email. You can securely message him on Signal by using his username, Miko Santos.

Sustaining Mencari Requires Your Support

Independent journalism costs money. Help us continue delivering in-depth investigations and unfiltered commentary on the world's real stories. Your financial contribution enables thorough investigative work and thoughtful analysis, all supported by a dedicated community committed to accuracy and transparency.

Subscribe today to unlock our full archive of investigative reporting and fearless analysis. Subscribing to independent media outlets represents more than just information consumption—it embodies a commitment to factual reporting.

Not ready to be paid subscribe, but appreciate the newsletter ? Grab us a beer or snag the exclusive ad spot at the top of next week's newsletter.