RBA Warns Rate Hikes Now on the Table—No Cuts Coming, Mortgage Pain May Get Worse

This piece is freely available to read. Become a paid subscriber today and help keep Mencari News financially afloat so that we can continue to pay our writers for their insight and expertise.

Today’s Article is brought to you by Empower your podcasting vision with a suite of creative solutions at your fingertips.

Reserve Bank Governor Michelle Bullock revealed December 9 that the board discussed circumstances for rate HIKES in 2026 and ruled out cuts entirely, saying inflation risks have “tilted to the upside” while the economy may already be running at capacity with little room to grow.

The shift that matters

The RBA kept the cash rate on hold at 4.35% as expected, but Governor Bullock’s press conference exposed a dramatic pivot: the bank didn’t even consider a rate cut and instead spent time mapping out “the circumstances and what might need to happen if we were to decide that interest rates had to rise again at some point next year” (RBA press conference, Sydney, December 9, 2025).

When asked directly by Reuters whether the board considered cuts or hikes, Bullock was blunt: “We didn’t consider the case for a rate cut at all” (RBA press conference, December 9, 2025). Instead, she warned that if inflation stays persistent beyond temporary factors, “the Board might have to consider whether or not it’s appropriate to keep interest rates where they are or in fact at some point raise them”

Why it matters to me (Gen Z): If you’re trying to save a deposit or already locked into a variable-rate mortgage, this means your situation could get worse before it gets better. The RBA just ruled out relief and flagged that the next move is more likely to be a rate increase than a decrease—meaning higher repayments, higher rents, and deposit targets that keep climbing faster than your savings.

Truth matters. Quality journalism costs.

Your subscription to Mencari directly funds the investigative reporting our democracy needs. For less than a coffee per week, you enable our journalists to uncover stories that powerful interests would rather keep hidden. There is no corporate influence involved. No compromises. Just honest journalism when we need it most.

Not ready to be paid subscribe, but appreciate the newsletter ? Grab us a beer or snag the exclusive ad spot at the top of next week's newsletter.

The inflation problem

Headline inflation sits at 3.8%, well above the RBA’s 2–3% target band. Bullock acknowledged that September quarter inflation “came in a bit stronger than expected” with “some temporary factors, but there were signs of persistence in some items” . The board is “alert to the signs of a more broad-based pick-up in inflation” rather than one-off spikes.

Critically, Bullock explained the board has concluded “the balance of risk to inflation had tilted a bit to the upside” while “downside risks, particularly from overseas, seem to abate it a little bit” (RBA press conference, December 9, 2025). Translation: inflation getting worse is now seen as more likely than inflation fading quickly.

When Bloomberg asked about the likelihood of cuts in 2026, Bullock shut it down: “Given what’s happening with underlying momentum in the economy, it does look like additional cuts are not needed. The private economy is recovering. It’s taking over from public demand”

What “tight” and “balance” actually mean

Bullock repeatedly referenced the economy being at or near “balance,” which in central bank speak means demand roughly equals supply—there’s no spare capacity. More concerning, she suggested the economy “might even be a little bit tight,” meaning demand could already be exceeding what the economy can sustainably produce

What is economic “balance”? When an economy is “in balance,” unemployment is low without causing runaway wage growth, and businesses can meet demand without excessive price increases. When it’s “tight,” demand outstrips supply, pushing up prices and wages faster than productivity growth can support—exactly the conditions that trigger central banks to raise interest rates.

The problem: “If demand really takes off from here and we’re already in balance, that’s a challenge”.Bullock noted Australia didn’t raise rates as high as other countries (which hit 5%+), “so we possibly had not as far to come back as other countries”.

The RBA’s assessment: the economy is already growing at about its potential, “so there’s not much more room for the economy to grow much more strongly” unless supply capacity somehow improves. That’s why stronger private demand—which would normally be good news—now creates inflation risk.

Private sector recovery creates a trap

Bullock highlighted that “growth in private demand was a bit stronger than expected, largely driven by business investment” . This is what both Chalmers and the RBA have been wanting—the private sector taking over from government spending as the driver of growth.

But here’s the catch: if the economy is already at capacity and private demand accelerates, the RBA may have to raise rates to prevent overheating. Bullock acknowledged this bind explicitly, saying the board discussed “how restrictive are financial conditions” and whether current rates are tight enough if inflation persists.

The political blame game intensifies

Federal Treasurer Jim Chalmers seized on Bullock’s comments about private sector recovery to attack the Coalition, claiming “absolute rubbish from our political opponents who say that the bank is focused on public spending.” He emphasized there was “no mention whatsoever of public spending in today’s statement” and that “the heavy lifting in our economy is now being done by the private sector” .

Shadow Treasurer Ted O’Brien rejected this entirely, arguing “the more money the government pours into the economy, the more it competes with households and with businesses” and insisting “the government has to stop that spending spree because if it doesn’t, the Reserve Bank cannot reduce interest rates”.

Neither politician directly addressed Bullock’s core message: the problem isn’t just demand-side spending (public or private), it’s that the economy’s supply capacity may be too constrained to handle stronger growth without triggering inflation.

Energy rebates and the inflation mirage

Bullock explicitly addressed electricity rebates, which have been temporarily suppressing headline inflation. “Rebates temporarily lower headline inflation and as they roll off, the headline inflation will move higher. The board looked through these effects when rebates were put on and is going to do so again as they come off”

This matters because Chalmers announced energy rebates are being phased out. When they disappear, headline inflation will jump even if underlying price pressures stay constant. Bullock made clear the RBA won’t be fooled: they’ll look past the rebate-related spike just as they looked past the rebate-related dip.

O’Brien attacked Labor over the rebate phase-out, claiming “the Australian people are just about to feel the full brunt of Labor’s failed energy policy” and that energy prices have risen “around 40%” while Labor “spent $6.8 billion papering over their failed energy policy”

When pressed on whether ending rebates helps curb inflation, O’Brien conceded “it was inevitable that at some point those relief payments had to come off because they were camouflaging the real problem at hand” —a rare moment of agreement between government and opposition on fiscal policy.

What happens next: February decision looms

Bullock emphasized the February 2026 meeting will be critical: “Before the next meeting, we will receive more data on the labour market and inflation, including quarterly trimmed mean. These will be important inputs into our updated forecasts”

When asked if a rate hike in February is plausible if December quarter inflation comes in high, Bullock wouldn’t rule it out: “If the inflation pressures look, when we get more data, they look to be persistent and they look to be not in one-off items, then I think that does raise some questions” about labour market tightness and whether financial conditions are restrictive enough

She refused to put a timeline on potential hikes but stressed “it’s going to be a meeting by meeting decision”

The soft landing that wasn’t soft enough

Bullock described Australia’s economic management as “pulling off a pretty impressive performance in bringing in a soft landing” by avoiding recession and keeping unemployment low (RBA press conference, December 9, 2025). But she acknowledged this success creates new problems: “Entering an economic upswing when you’ve got very low unemployment, you’ve got capacity utilization reasonably high” means there’s not much room for growth to accelerate (RBA press conference, December 9, 2025).

The “narrow path” strategy—raising rates just enough to slow inflation without spiking unemployment—remains in place. But Bullock warned: “If we don’t get inflation back down to the target and inflation expectations start to rise, then that won’t be good for employment because we will have to raise interest rates quite a lot more and we will have to hurt the economy more”

Translation: the RBA will accept some pain now to avoid much worse pain later.

Gen Z impact line:

If you’re under 30, the RBA just killed any hope of rate cuts in 2026 and signaled hikes are more likely—meaning mortgage calculators won’t work in your favor, rents will keep climbing as landlords pass on higher costs, deposit targets will keep moving, and your power bill is about to jump when energy rebates end, all while politicians argue over who’s to blame instead of fixing the housing crisis.

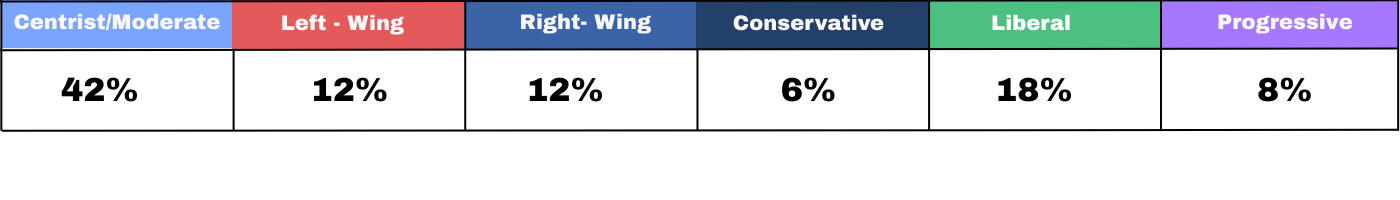

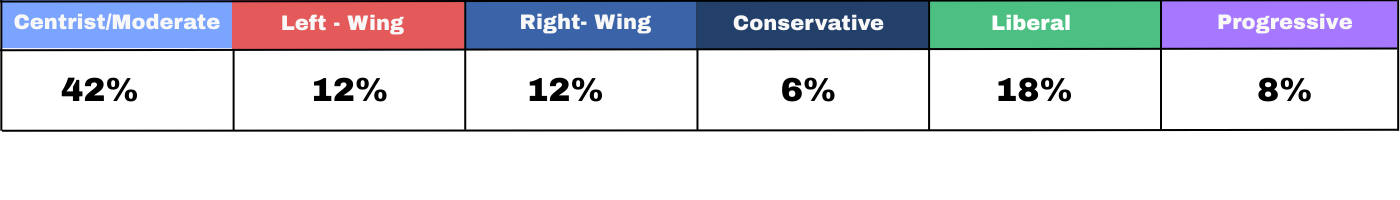

Bias Explanation: This piece leans heavily Centrist/Moderate-Liberal because it centers the RBA (an independent technocratic institution) and foregrounds institutional monetary policy over partisan narratives, while including Labor and Coalition perspectives in roughly equal measure as secondary commentary. The focus on central bank independence, data-driven decision-making, and technical economic concepts (capacity constraints, supply-side limits, trimmed mean inflation) reflects liberal-technocratic framing rather than redistributive or market-fundamentalist ideology.

Bias comparisons derive from an AI-assisted evaluation of content sources and are protected by copyright held by Mencari News. Please share any feedback to newsdesk@readmencari.com

Sustaining Mencari Requires Your Support

Independent journalism costs money. Help us continue delivering in-depth investigations and unfiltered commentary on the world's real stories. Your financial contribution enables thorough investigative work and thoughtful analysis, all supported by a dedicated community committed to accuracy and transparency.

Subscribe today to unlock our full archive of investigative reporting and fearless analysis. Subscribing to independent media outlets represents more than just information consumption—it embodies a commitment to factual reporting.

It only takes a minute to help us investigate fearlessly and expose lies and wrongdoing to hold power accountable. Thanks!