Expert Proposes "Hateful Extremism" Laws to Combat Online Hate — But Warns Crackdowns Could Drive Radicalization Underground

This piece is freely available to read. Become a paid subscriber today and help keep Mencari News financially afloat so that we can continue to pay our writers for their insight and expertise.

Today’s Article is brought to you by Empower your podcasting vision with a suite of creative solutions at your fingertips.

Australia should criminalize “hateful extremism” even when it doesn’t cross into violence, a leading counter-terrorism expert told Sky News Wednesday — but he also warned that harsh crackdowns on protests and speech could backfire by pushing extremists into “dark corners of the internet” beyond surveillance.

The policy proposal from Josh Roose, a terrorism expert who has worked extensively with the Jewish community, represents a significant expansion of government authority to prosecute hate speech both online and offline. It comes as state and federal governments rush to pass emergency laws responding to Sunday’s Bondi Beach attack that killed 15 people.

But Roose’s comments also highlighted a central tension in the response: How do democracies combat extremism without inadvertently making the problem worse?

“I worry that it’ll make us feel safe, but not actually be safe,” the Sky News interviewer said, raising concerns that restricting outlets for expression could push people toward radicalization out of plain sight. “Do they go to dark corners of the internet and then radicalise out of plain sight?”

Roose acknowledged the complexity: “We are in a democracy. People need to be able to express their opinions no matter how offensive many might find them.”

The Hateful Extremism Threshold

Under current Australian law, authorities can only act against individuals who cross into “violent extremism” — essentially, when they advocate or plan physical violence. This threshold has allowed extremist groups to operate legally as long as they avoid explicit calls for violence.

Roose proposed lowering that threshold to “hateful extremism,” which would criminalize speech that “dehumanises others” or attacks people “on the basis of a characteristic in a hateful manner.”

“That then deals with your Nazis, your hate groups, like Hizb ut-Tahrir, that spread hate but don’t cross a line into violent physical extremism and who generate an atmosphere of hate,” Roose said.

Hizb ut-Tahrir is an Islamist organization banned in Germany, the United Kingdom, and several Muslim-majority countries but remains legal in Australia. Nazi groups that conducted demonstrations on state Parliament steps in recent weeks would also fall under the proposed law.

The policy would apply both online, “where it’s running absolutely rampant,” and offline at protests and demonstrations.

What is “hateful extremism”?

A proposed legal category below “violent extremism” that would capture dehumanizing rhetoric, attacks based on identity characteristics, and hate speech that creates what Roose called “an atmosphere of hate”—without requiring direct incitement to physical violence. No Australian jurisdiction currently has this threshold; it would represent a significant shift in free speech boundaries.

International Precedents

Roose cited recent action in the UK, where Manchester authorities banned use of the term “intifada” at protests — a move that sparked debate about whether restricting specific words effectively combats extremism or simply forces it into less visible spaces.

Critics of such bans argue they create martyrs and drive organizing onto encrypted platforms where authorities have less visibility and communities have less ability to counter extremist messaging.

The Intelligence Failure Timeline

Roose also revealed new details about how the Bondi Beach attack was allowed to happen despite warning signs dating back six years.

The shooter “had come onto the radar over six years ago as a known associate of extremists, including Islamic State terrorists,” Roose said. “At that point, there should have at least been some sort of flagging in the system that this individual ever popped up again, there’d be some form of surveillance or action.”

That timeline — 2019, as previously confirmed by the AFP — means the attacker was flagged during the height of ISIS operations in Iraq and Syria, when Australian authorities were actively tracking citizens with extremist links.

The failure wasn’t just intelligence gathering. It was systems integration: information existed but didn’t trigger action when the individual later accumulated firearms or traveled to the Philippines for military training.

The Family Gun Arsenal Problem

Roose also identified a gap in current firearms legislation: close family members of known extremists can accumulate weapons legally.

“In respect to the ability of his father to accumulate firearms as a close family member of someone with extremist links, there’s also significant issues there,” Roose said.

This detail adds complexity to the gun reform debate. Current NSW proposals would cap total firearms ownership and eliminate appeals when licenses are revoked — but they don’t address whether police should automatically scrutinize family members of flagged individuals.

Should having a son on an extremist watchlist disqualify a father from gun ownership? Current law says no. Roose suggests that needs examination.

Royal Commission: “We Can’t Put Band-Aids on It”

Beyond immediate legislative fixes, Roose called for a Royal Commission to “join the dots on how we got to this moment and not only the role of different actors in it, but where to from here.”

“We have to look at this in a much more substantive manner,” Roose said. “We can’t put band-aids on it and hope that this is going to go away. We have to unpack it and build an evidence base for further policy going forward.”

A Royal Commission would have subpoena power to compel testimony from intelligence agencies, police, and government officials about what they knew, when they knew it, and why intervention didn’t occur. It would also examine the “deeper-seated underpinnings” of rising anti-Semitism and extremism in Australia over the past two years.

Former Treasurer Josh Frydenberg called for a Royal Commission into anti-Semitism in his emotional Bondi Beach speech Tuesday. NSW Premier Chris Minns said Wednesday his government is “contemplating that at the moment” but noted it’s complicated by the need to ensure nothing interferes with the criminal prosecution of the surviving attacker.

The Central Dilemma

Roose’s interview crystallized the challenge facing Australian policymakers: Extremism requires a response, but the wrong response could make things worse.

Too little action — the current approach of only prosecuting violent extremism — allowed Hizb ut-Tahrir, Nazi groups, and ISIS-inspired individuals to operate until violence occurred.

Too much action — banning protests, criminalizing broad categories of speech — could push extremists underground where they’re harder to monitor and counter.

The “hateful extremism” proposal attempts to thread that needle by expanding criminalization while maintaining democratic principles. Whether it succeeds depends on how it’s defined and enforced — details that will be debated as governments rush to pass emergency legislation in coming weeks.

For young Australians who have grown up with social media, participate in online communities, and expect to protest issues they care about, these debates aren’t abstract. They’re about what speech remains legal, what organizing is permitted, and how much authority government should have to police expression in the name of safety.

The NSW Parliament will debate some of these measures December 22-23 in emergency session. But as Roose noted, the deeper work — understanding how Australia reached this point and building evidence-based policy for the future — requires the thorough investigation only a Royal Commission can provide.

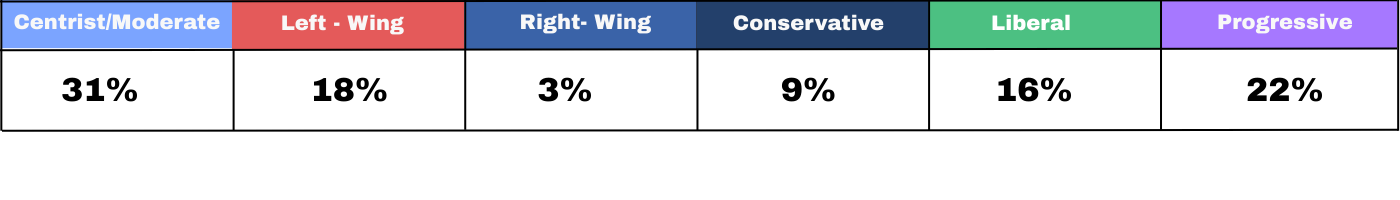

Bias Explanation: This piece skews Centrist/Progressive because it platforms a security expert calling for state intervention to limit hate speech—a progressive policy goal—but frames it through national security and institutional reform (centrist framing) rather than social justice movement demands. The expert acknowledges democratic free speech principles while arguing for narrower restrictions, which bridges liberal and progressive positions. Right-wing and conservative perspectives on free speech expansion are absent—no quotes from civil liberties advocates or groups who’d oppose this threshold lowering.

Bias comparisons derive from an AI-assisted evaluation of content sources and are protected by copyright held by Mencari News. Please share any feedback to newsdesk@readmencari.com

Sustaining Mencari Requires Your Support

Independent journalism costs money. Help us continue delivering in-depth investigations and unfiltered commentary on the world's real stories. Your financial contribution enables thorough investigative work and thoughtful analysis, all supported by a dedicated community committed to accuracy and transparency.

Subscribe today to unlock our full archive of investigative reporting and fearless analysis. Subscribing to independent media outlets represents more than just information consumption—it embodies a commitment to factual reporting.

Not ready to be paid subscribe, but appreciate the newsletter ? Grab us a beer or snag the exclusive ad spot at the top of next week’s newsletter.