Australia's $33B deficit sparks calls to cut spending, not raise taxes

This piece is freely available to read. Become a paid subscriber today and help keep Mencari News financially afloat so that we can continue to pay our writers for their insight and expertise.

Today’s Article is brought to you by Empower your podcasting vision with a suite of creative solutions at your fingertips.

Australia’s budget deficit has ballooned to nearly $33 billion, with Treasurer Jim Chalmers set to release a mid-year update next week. Government spending on wages and programs like the NDIS is outpacing revenue growth, triggering debate about whether to cut costs or increase taxes.

The budget deficit has hit $33 billion. Here’s what that means for under-35s.

Australia’s federal budget is bleeding red ink. As of October, the deficit reached nearly $33 billion—and Treasurer Jim Chalmers will release the full mid-year update next week that could show it’s even worse.

The core issue: government spending, especially on public sector wages, is growing faster than the revenue coming in to pay for it. That creates a fiscal gap that has to be filled somehow—either by cutting spending, raising taxes, borrowing more, or selling assets.

What is NDIS and why does it matter?

The National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) provides funding and support for Australians with permanent and significant disabilities. It’s one of the government’s largest and fastest-growing expense lines. According to Associate Professor Mark Humphrey-Jenner from UNSW Business School, NDIS spending is currently growing at roughly double the rate of GDP growth. When a program expands that much faster than the economy, it becomes mathematically difficult to sustain without major reforms or revenue increases elsewhere.

Truth matters. Quality journalism costs.

Your subscription to Mencari directly funds the investigative reporting our democracy needs. For less than a coffee per week, you enable our journalists to uncover stories that powerful interests would rather keep hidden. There is no corporate influence involved. No compromises. Just honest journalism when we need it most.

Not ready to be paid subscribe, but appreciate the newsletter ? Grab us a beer or snag the exclusive ad spot at the top of next week's newsletter.

The spending side: where the money’s going

Beyond NDIS, energy subsidies introduced before the last election are now unwinding, which will reduce some spending. But other pressures are mounting. Defence spending is under scrutiny because the United States—Australia’s primary security ally—wants NATO-style defence commitments of around 3.5% of GDP. Australia currently spends less than that, but the AUKUS submarine deal (which involves direct payments to the US) has provided some political cover.

To find quick cash, the government is reportedly considering selling defence real estate like Paddington Barracks in Sydney. Humphrey-Jenner warned that selling assets to cover operating expenses is short-term thinking: “It’s like selling your house to pay your mortgage—you still need somewhere to live.”

Another spending problem: the size of the public sector itself. According to the interview, 80% of new jobs created in Australia now depend on the “non-market sector”—meaning they’re either directly government jobs or funded by government contracts. Every time the bureaucracy expands, it adds not just salaries but travel, offices, and administrative overhead. Humphrey-Jenner cited examples like eSafety Commissioner Julie Inman Grant spending over $1 million on international travel, and Youth Minister Anika Wells spending $100,000 to deliver a six-minute speech in New York.

The revenue side: why raising taxes might backfire

On the revenue side, Australia faces a warning from the UK. When UK Chancellor Rachel Reeves hiked capital gains tax rates to fill budget holes, capital gains tax receipts actually fell by 10%. Why? Wealthy individuals moved money out of the country, and transaction volumes dropped because people held onto assets longer to avoid the tax hit.

Australia already has the highest capital gains tax rate in the world—47% at the top marginal rate, or 23.5% for long-term holdings. That’s higher than China (20%), Vietnam (replaced CGT entirely with a 2% transaction tax), and zero-tax jurisdictions like Hong Kong, Singapore, and New Zealand. A capital gains tax review is scheduled for next year, and Humphrey-Jenner fears policymakers will follow the UK into what he calls a “death spiral”—raising rates, losing revenue, raising rates again.

The alternative prescription: grow the economy by cutting red tape and regulatory burdens, rather than extracting more from existing activity.

What different sides are saying

Government position (Labor, centre-left): Treasurer Jim Chalmers has not yet released the mid-year update, so the official response is pending. Labor traditionally favours maintaining social programs like NDIS and negotiating with stakeholders on reforms.

Pro-market economists (represented by UNSW’s Humphrey-Jenner): Focus should be on reducing government sector growth, avoiding tax hikes, and pursuing growth-oriented reforms. They argue Australia’s tax rates are already uncompetitive globally and that further increases will drive capital and talent offshore.

Defence hawks: Pressure from the US (particularly under a Trump administration) to increase defence spending to 3.5% of GDP creates a budget squeeze unless other programs are cut or revenues rise significantly.

What this likely means next

When Chalmers releases the mid-year budget update, expect three possible responses:

Austerity measures: Caps on public sector hiring, efficiency reviews, or program cuts (politically difficult in an election cycle).

Tax increases: Potential adjustments to capital gains tax, superannuation taxes, or other revenue measures (risks UK-style backfire).

Asset sales: Quick cash from selling government property or equity stakes in public enterprises (one-time fix that doesn’t solve structural imbalances).

The political calendar matters. With a federal election due by May 2025, neither major party wants to deliver painful budget news that could cost votes. That creates an incentive to delay tough decisions or use accounting tricks to make the numbers look better temporarily.

For young Australians, this matters because fiscal imbalances today mean either higher taxes or reduced services in the future. If the government can’t control spending growth or find sustainable revenue sources, the bill gets passed forward—and Gen Z will be the ones paying it.

What Gen Z can do next

Check the mid-year budget update when it drops: Look for the deficit projection, where spending increases are coming from, and what revenue assumptions are being made. Treasury’s website will have the full document.

Compare capital gains tax internationally: Use PWC’s global tax tables (linked in our show-your-workings section) to see how Australia stacks up. If you’re considering starting a business or investing, this affects your after-tax returns.

Track your local MP’s position: Are they pushing for spending discipline, or defending specific programs? Their stance now will shape what happens post-election.

Understand NDIS reform debates: If you or someone you know relies on NDIS, follow consultation processes and participate. The scheme’s sustainability matters for disability support and the budget.

Why it matters to me (Gen Z)

If you’re under 35, this budget squeeze will shape your financial reality for the next decade. Higher taxes mean less take-home pay and lower investment returns. Spending cuts could hit university funding, first-home buyer schemes, or youth employment programs.

And if the government sells assets now to cover short-term gaps, there’s less public infrastructure (land, buildings, equity stakes) generating revenue in the future—meaning either higher taxes or worse services when you’re in your peak earning years. The decisions made in the next 6-12 months set the fiscal baseline for your 30s and 40s.

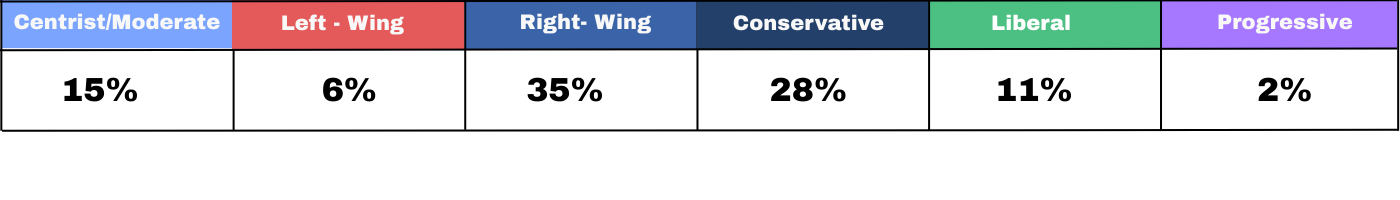

Bias Explanation: This piece leans heavily Right-Wing and Conservative because it centres a pro-market economist who advocates cutting government spending, opposes tax increases, and frames public sector growth as “bloat.”

The policy prescriptions emphasise deregulation and economic growth over redistribution or social programs. Source mix includes a business school academic and a Sky News platform (both typically centre-right to right in Australia), with limited progressive or labour-aligned voices. The framing uses efficiency/fiscal discipline language rather than equity or social justice frames.

Bias comparisons derive from an AI-assisted evaluation of content sources and are protected by copyright held by Mencari News. Please share any feedback to newsdesk@readmencari.com

Sustaining Mencari Requires Your Support

Independent journalism costs money. Help us continue delivering in-depth investigations and unfiltered commentary on the world's real stories. Your financial contribution enables thorough investigative work and thoughtful analysis, all supported by a dedicated community committed to accuracy and transparency.

Subscribe today to unlock our full archive of investigative reporting and fearless analysis. Subscribing to independent media outlets represents more than just information consumption—it embodies a commitment to factual reporting.